The Art of the Motorcycle

11.24.1999 - 09.03.2000

One hundred and thirty years ago neither the bicycle nor the engine existed in the forms we are familiar with. In 1868 Louis Perreaux patented a design for a steam engine installed in the first commercially successful pedal bicycle; by 1894, the Hildebrand brothers and Alois Wolfmüller had patented a water-cooled, two-cylinder gasoline engine in a bicycle type frame, the first commercially produced motorcycle with an internal combustion engine.

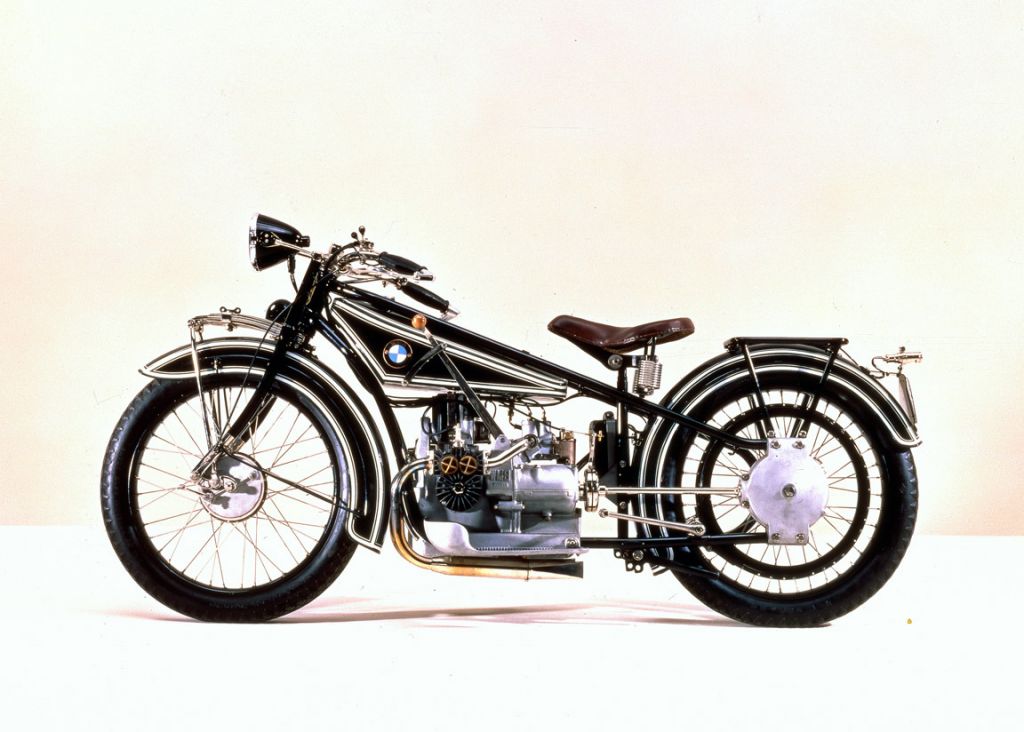

The Art of the Motorcycle not only spans the century of motorcycle production that evolved from this moment, but the technological progress and cultural, sociological and economic factors that define and characterize the twentieth century. In addition to these, commerce, marketing and the expectations and desires of consumers are all manifested in the components and form of the motorcycle. The sheer number of available motorcycles-production models, factory-built specials, customized one-offs, side-cars and tricycles-is vast. To extract a narrative from the array of functions and dictates that motorcycles represent, the choices were refined to a group of singularly twentieth century defining elements, aesthetics, technological innovation, design excellence, and social impact. All of the motorcycles in the exhibition are a product of more than one of these criteria, some, like the BMW R32 or the Honda Super Cub, are a harmonious combination of all three.

One of the most significant steps forward in engine technology, as well as an example of the design aesthetic of its era, is the BMW R32. To look at this brilliant little design, the work of aeronautical designer, Max Friz, is to see the groundwork for the success of BMW motorcycles for the rest of this century. To this day, the mainstay of BMWs motorcycle range is the unburstable transverse flat twin ("Boxer") engine, first introduced in the R32 in 1923. In the BMW R32, all the ideals of the Bauhaus seem present and the style emerges effortlessly from its craftsman-like triangular lines. This is a machine that, sotto voce, asks in equal measure to be ridden and to be admired.

Subtlety is not the Indian Chief's most obvious suit. Big, brash and showy, it was the epitome of American motorcycling ideal. Although first designed in the 1920s, the Indian Chief came into its own in 1940 with the addition of its trademark fenders, deep and curvaceous. This was a bike for the fugitive spirit, for taking to the road and never turning back. Once on the road, it did its business handsomely, the enormous 74-cubic-inch engine capable of speeds close to 100 mph. The Indian Chief was one of the original luxury liners of American motorcycling and it established a cruiser aesthetic which is still being followed today, principally by its former archrival, Harley-Davidson.

"You meet the nicest people on a Honda." This was the iconic slogan which completely broke the mold of motorcycle marketing in the early 1960s and, just as deftly, broke Honda into the enormous American market. Things were never quite the same after that. But it was not an enormous muscle bike that spearheaded Honda's push into the West, but a diminutive, step-through 50cc motorcycle with an automatic clutch and cute red and cream styling. It was the kind of bike your mom wouldn't mind you riding; in fact, it was the kind of bike your mom could ride! The Honda C100 Super Cub, to give it its full title, was founder Soichiro Honda's brilliant little Trojan horse and paved the way for a complete revolution in motorcycle sales in the ensuing years. It's hard to believe now but, at the time, Honda 50s were laughed at. Twenty six and a half million Honda 50s later, no-one's laughing! (Read that again: 26.5 million Honda Super Cubs.) Except, perhaps, the designers at Honda, who allow themselves the wry smile in recognition of Soichiro Honda's audacity in thinking that he could change the world. Truth is, he could and did.

It is ironic that Honda's success spelt doom for the British motorcycle industry, which was too slow to react to the new Japanese standards of production, design and marketing. Among the best bikes from that hallowed tradition was the Triumph Bonneville, named after the salt flats in Utah where countless speed records have been set and challenged. This was deliberate on the part of Triumph. They wanted to give their quintessentially British bike an American twang, and the Bonneville hit the spot perfectly. The bikes were the love of a generation of American bikers and the Triumph name was canonized in films like The Wild One and The Greart Escape. The curse of the Triumph, an otherwise lovely, light and very quick design from Edward Turner (one of the great motorcycle designers of all time) was vibration. All vertical twins suffer from it, and the bigger the engine, the more pronounced the vibration. The rattling was actually considered to be part of the charm until Honda came along with the turbine-smooth, four-cylinder CB750. Honda's success was Triumph's death-knell, and its end came fairly quickly. Today, the Triumph name has been revived, but the mystique of old is still exemplified in the Bonneville.

Three Spanish motorcycles represent the brilliance and adaptability of Spanish motorcycle designers: the Bultaco Sherpa T, the Derbi 50 Grand Prix and the Gas Gas.

The Derbi 50 Grand Prix bike is a marvel of speed and precision. That it was based on a bike, the Antorcha, that was the most commonplace little moped of all, is even more remarkable. The Derbi 50 is a watchmaker's delight; small, light, precise. Most important, in the hands of a genius like Angel Nieto, it was very very fast-too fast for the competitors in the far richer Kreidler and Suzuki teams.

Two other Spanish bikes show how design brilliance can change a sport completely. Until the mid '60s, the sport of trials, where riders negotiate special tests' over difficult ground, was dominated by large, British four-stroke machines: Ariels, Matchlesses and Nortons. Sammy Miller, the greatest all-round rider of his day, decided that these bikes were far too heavy to have a future, and he worked with Spanish designer Francisco (Paco) Bultó to produce the first Bultaco Sherpa for the trials season in 1965. This bike not only revolutionised trials competition in Britain, it became the most successful trials design of all time and opened up the sport throughout Europe and the United States.

In Spain, inspired by men like Sammy Miller (and Malcolm Rathmell on his Montesa), Jordi Tarres wanted to ride trials, but he was too young. Instead, he rode Trial Sin, the bicycle version of the sport where he developed his trademark acrobatics: the bunny hop to jump over obstacles, and the art of moving the bicycle around a single spot while remaining in complete control. When it came to riding motorcycle trials, Tarres brought all this ability to bikes that were too heavy for his liking. The Gas Gas on which he won his world championships is little more than a perfect bicycle with an engine (how motorcycle design has come full circle in a hundred years!). It is incredibly light, has no seat (trials riders perform standing up!), and can be made to vault up seemingly impossible vertical sections with the flick of a wrist.

The Britten V-1000 is packed with mystique, partly due to the tragic early death of its engineer/designer. New Zealander John Britten was the maverick genius of modern motorcycle design. Beginning in the late 80s and continuing until his death from cancer in 1995, Britten stood the world of racing motorcycle design on its head with his radical and successful racing motorcycle.

Britten's hand-built machine was assembled around his own 1000cc 60E V-twin engine. Beautifully designed, the engine is light, immensely strong, incredibly smooth for a V-twin, and powerful, developing 160 bhp at 11,500 r.p.m. The engine is the heart and soul of the Britten and all the external design decisions flow from it. Most radical of all was Britten's decision not to use a conventional frame. Instead, using Kevlar and Carbon fiber, everything from seat to wheels to suspension was bolted to the engine which became the central stressed unit. The seat itself is simply a carbon fiber beam extending rearward from the cylinder head. The rear suspension is actually mounted in front of the engine, and connects to the rear swingarm, again a composite, via a long rod. The intention was to cluster as much of the weight as possible around the engine, giving a short-coupled and quick-handling motorcycle.

All this engineering wizardry might have ended up looking like a techno-geek's nightmare. With its almost organic, coiled-spring compactness, Britten's genius was as much to turn his dream into a thing of beauty as to have it win races. It succeeded on both counts and remains perhaps the most influential racing motorcycle of the '90s.

Ultan Guilfoyle

Assistant Curator

The Art of the Motorcycle

BMW R32, Germany, 1923

494 cc